Placeful is a weekly newsletter exploring sense of place, sustainability, and the actions we can take to more deeply engage with our communities and wild spaces. Each week covers a new topic. To learn more about the “why” behind Placeful, start here.

Any books mentioned in this issue may be found on my bookshop shelf. I may earn a commission from books purchased through these links, at no additional cost to you.

In spring of 2017, a younger, recently graduated version of me drove across the Rocky Mountains, following the Colorado River through Glenwood Canyon, past the Book Cliffs near Grand Junction, eventually reaching my final destination: Moab, my little desert home. I was thrilled to be starting my internship at the Youth Garden Project, where I would spend six months learning the ins and outs of small-scale organic agriculture in the desert.

During the first week, my supervisor took us on a tour of the native plant garden surrounding the main office at YGP, which boasts a healthy array of native plant species. We learned about claret cup cacti, desert willow, baskets-of-gold, chocolate flower, and firecracker penstemon, among other beautiful, drought-tolerant species.

Very knowledgable about all things plants, my supervisor explained that the firecracker penstemon can be identified by the arrangement of their leaves—two across from each other, alternating 90 degrees as they sprout off the stem.

She also explained the descriptive Greek-derived name, which identifies the penstemon flower as having five stamen. One of the stamen is sterile and more visually dynamic than the others.

A few weeks later, my roomates and I were hiking along Grandstaff Canyon, a popular spot among locals and tourists in Moab, and what do you know—we came across a firecracker penstemon in the wild! I first noticed the eye-catching color of the flowers, and on further inspection, recognized the familiar alternating leaf pattern.

It’s a small thing really, identifying a plant, but this marked a huge turning point for me. It was a goal of mine to learn the names of more native species, but between moving so often and not having the right mentors, this pursuit had rested on the backburner for a long time.

But finally, something I had learned at my internship was spilling over into my experiences exploring the canyon country. Knowledge gained in an educational environment, now in context. It felt like running into an old friend. I took a photo to mark the occassion, and it still serves as my laptop screensaver to this day. In later months and years, I had similar experiences with russian sage, globe mallow, and many more native SW plant species I was introduced to that season.

There is a name for the process of familiarization with our local ecosystem: bioregionalism, and it’s one of the foundational inspirations for me in beginning this writing project.

In this issue of Placeful, I’ll be introducing the topic of bioregionalism, including the benefits to us as individuals, as well as the benefit that this pursuit can have for our communities and wild spaces when our bioregional knowledge is used for good.

In the spirit of finding old friends in new places, let’s get started. And if you enjoy what you read here, I hope you’ll consider sharing this issue, too!

What is bioregionalism?

In How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, author Jenny Odell writes,

Similar to many indigenous cultures’ relationship to land, bioregionalism is first and foremost based on observation and recognition of what grows where, as well as an appreciation for the complex web of relationships among those actors.

As Odell makes sure to highlight, bioregionalism is a not a new concept. It describes what has been the traditional (and necessary) way of life for many people across the world for thousands of years. It is an understanding of the other living beings with whom we share our places. Odell continues,

More than observation, it also suggests a way of identifying with place, weaving oneself into a region through observation of a responsibility to the local ecosystem (Asked where he was from, Peter Berg, an early proponent of bioregionalism, used to answer: “I am from the confluence of the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River and San Francisco Bay, of the Shasta bioregion, of the North Pacific Rim of the Pacific Basin of the Planet Earth.”) In these ways, bioregionalism is not just a science, but a model for community.

If I were to follow Peter Berg’s lead, I might say that I live along the Colorado River, within the Moab Valley of the Arid Canyonlands, of the Sonoran bioregion, of the Colorado Plateau. It’s an area dominated by piñon, juniper, and rabbitbrush, of red rock walls cut out and pushed around by millions of years of wild rivers and geologic activity and the inevitabile results of gravity & time.

If we were to follow Peter Berg’s lead in another way, he would also show us that bioregionalism is more than memorizing names and places, more than knowing the geography, watershed, physiography, or local flora and fauna of a place and the ecological communities it supports. It also has a cultural element: “A bioregion refers both to geographical terrain and a terrain of consciousness — to a place and the ideas that have developed about how to live in that place” (Peter Berg & Raymond Dasmann, Reinhabiting a Separate Country, 1978).

Looking at our homes through a bioregional lens is a paradigm shift, a new rendering of our surroundings. Like the phenomenon of learning a new word and then seeing it everywhere, bioregionalism gives us the chance to experience our reality in an expanded way:

Redwoods, oaks, and blackberry shrubs will never be “a bunch of green.” A towhee will never simply be “a bird” to me again, even if I wanted it to be. And it follows that this place can no longer be any place.” (Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing, 2019)

Bioregionalism in practice

Now that we understand what bioregionalism is, let’s explore a few ways this concept might have real world outcomes if widely understood, valued, and pursued.

Bioregionalism on the individual level

A while ago, I came across a quote about plant blindness—the inability to name, appreciate, and register the plant life around us. I cannot remember for the life of me who said it or where to find it again, but the core of it was that it must be so lonely [for people of Western societies especially] to exist in a world where they don’t know the names of most plants and animals. And to this I say, yes. It’s my personal belief that bioregionalism can contribute to a sense of belonging, and in turn, to our individual happiness.

Bioregionalism is the difference between intimately knowing our surroundings and feeling like we are in the midst of a vast, unknowable expanse. Between these two options, how could the first not be better for our mental and physical health? We already know that experiences in natural environments—whether its a multi-day camping trip or just looking at a tree outside a window—make us happier; this has been proven through research time and again. Bioregionalism takes it a step further.

Bioregionalism on the community level

Indigenous communities with a vast amount of bioregional knowledge were and are much better at taking care of our planet’s natural resources than Western societies have been. At the community level, I believe if more people took to heart the core concepts of bioregionalism, there would be fewer disputes over resource use. Bioregionalism necessitates a new way of seeing the world, not as a planet of individuals, but as a collective of connected living beings and natural systems with their own intrinsic value.

Here’s an metaphor I’ve been contemplating: for some folks, it’s hard to imagine slaughtering a chicken from our own coop that we have raised and named and loved. I believe if we know and appreciate the species within our bioregion—if we give them names and love them, too—we will do more to protect them. In the process, we might just create and maintain healthier communities for all.

Bioregionalism on the ecological level

I’d like to expand on the concept of resource use with a little story about the saguaro cactus. As many people know, the saguaro cactus is protected in Arizona; you cannot destroy a saguaro. If it is in the way of a development project, it must be relocated. Palo verde, mesquite, and ironwood trees are also protected through the Arizona Department of Agriculture Environmental Services Division. These plants are part of the same ecological community, and the existance of each depends heavily on the other.

When a saguaro seedling first emerges from its sandy soil bed, its chances of survival are heightened by the existance of a nearby nurse tree—often the palo verde, a beautiful desert tree with an identifiably green trunk. In fact, the saguaro seed likely ended up there after a bird nested in the palo verde’s branches and dropped a cactus seed while feeding cactus fruit to its babies. The palo verde tree provides protection from the intense desert sun and potentially harmful frosts in the first year’s of the saguaro’s life, as well as protection from potential tramplings by wandering desert creatures.

As the saguaro slowly grows up, its wide but shallow root system spreads—an adaptation that helps it take advantage of quick desert rains. Eventually the saguaro outcompetes the nurse tree for water, and the palo verde dies. Doesn’t seem very nice, but this is a Sonoran Desert reality. However, this is why we see saguaro cacti so spread out from each other, and why younger ones can be found nearby trees while older ones typically are not.

I love this story of the bird and the palo verde and the saguaro. It demonstrates how important all three are to the Sonoran Desert landscape. People are naturally fond of the eccentric saguaro cacti and palo verde trees, and take many precautions to protect them. Understanding that they are part of a more complex system informs Arizona’s native plant protection laws, and bioregionalism helps us advocate for them.

Bioregionalism in a globalized world.

In an economy where I can ship a cactus to my house from almost anywhere in the U.S. and eat food grown around the world, the concept of bioregionalism as a way of survival might not seem pertinent anymore. However, when we neglect this opportunity to better know our surroundings, we also miss out on the chance to belong to it wholeheartedly, and also to understand the bigger picture role it plays in making our shared planet survivable for all.

As with most of the things I write, I do not expect everyone to become an expert naturalist overnight. But I will advocate for a society in which everyone has a part to play, and where each child and adult engages in lifelong learning about the place where they live. Where we teach each other what we’ve learned along the way. Where we regain control over our attention, curiousity is celebrated, place-based education is the norm, and out interconnectedness is never taken for granted.

Where we can run into a wildflower like running into an old friend.

With love,

Emily

Placeful Practice

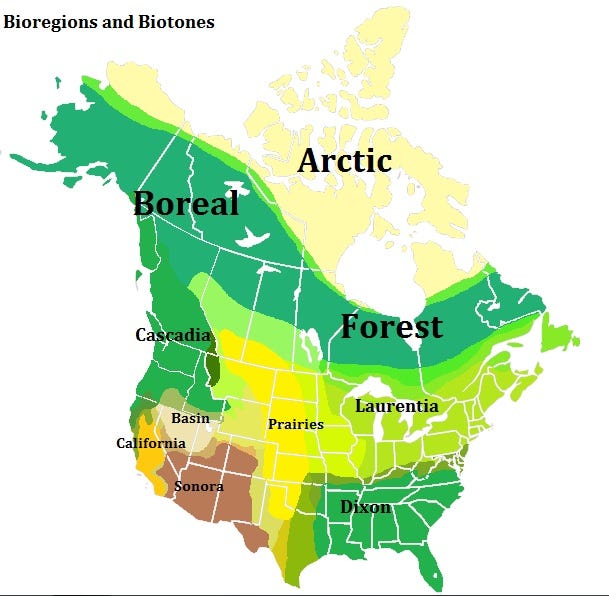

A good place to start this week is by identifying your bioregion on the map below. What is it called? Can you look up who the dominant plant or animal species are within it? These are good things to know to begin noticing patterns in your local environment.

For even more fun, here’s an interesting quiz from 1981: Where You At? A Bioregional Quiz

Have you shared a similar moment of recognition, like me and the firecracker penstemon? What moment stands out in your life as one where you felt most connected to your bioregion? Share with the Placeful community below, or shoot me an email at placeful.emily@gmail.com. I love to hear from y’all!

Somewhat unrelated, but cool

My friend recently opened a very cool online cactus and succulent shop. Like I said, you really can ship a cactus to your house from anywhere—in this case south Texas! Check it out if you want to support a Latinx & Indigenously owned and operated Xerophyte plant shop.

Placeful is a weekly email newsletter containing personal reflections and reporting on sense of place and sustainability. Each week I delve into a new topic, wrapping it up with an action item that will help readers foster deeper connections to the natural, cultural, built, and historic environments around them. Read more about Placeful.

To find a web version of this issue, click here. Know someone who would appreciate the topics I’m writing about? Please share! If you’d like, you can follow me on Twitter (@emily_ann_again) or Instagram (@emily.a.roberson). My inbox is always open at placeful.emily@gmail.com. And lastly, if someone forwarded this to you, subscribe below to receive future issues straight to your inbox. Thanks for reading <3