A part of, not apart from, nature | Issue #16

Addressing the dominant Western ideology of separation between people & nature. Also, reindeer 🦌

Placeful is a weekly newsletter exploring sense of place, sustainability, and the actions we can take to more deeply engage with our communities and wild spaces. Each week covers a new topic. To learn more about the “why” behind Placeful, start here.

Any books mentioned in this issue can be found on my bookshop shelf. I may earn a commission from books purchased through these links, at no additional cost to you.

Early in the pandemic, a meme was—as memes do—circulating around the internet. As people were posting about animals returning to cities, and carbon emissions slowing due to the economic slowdown, the punchline was “nature is healing, we are the virus.”

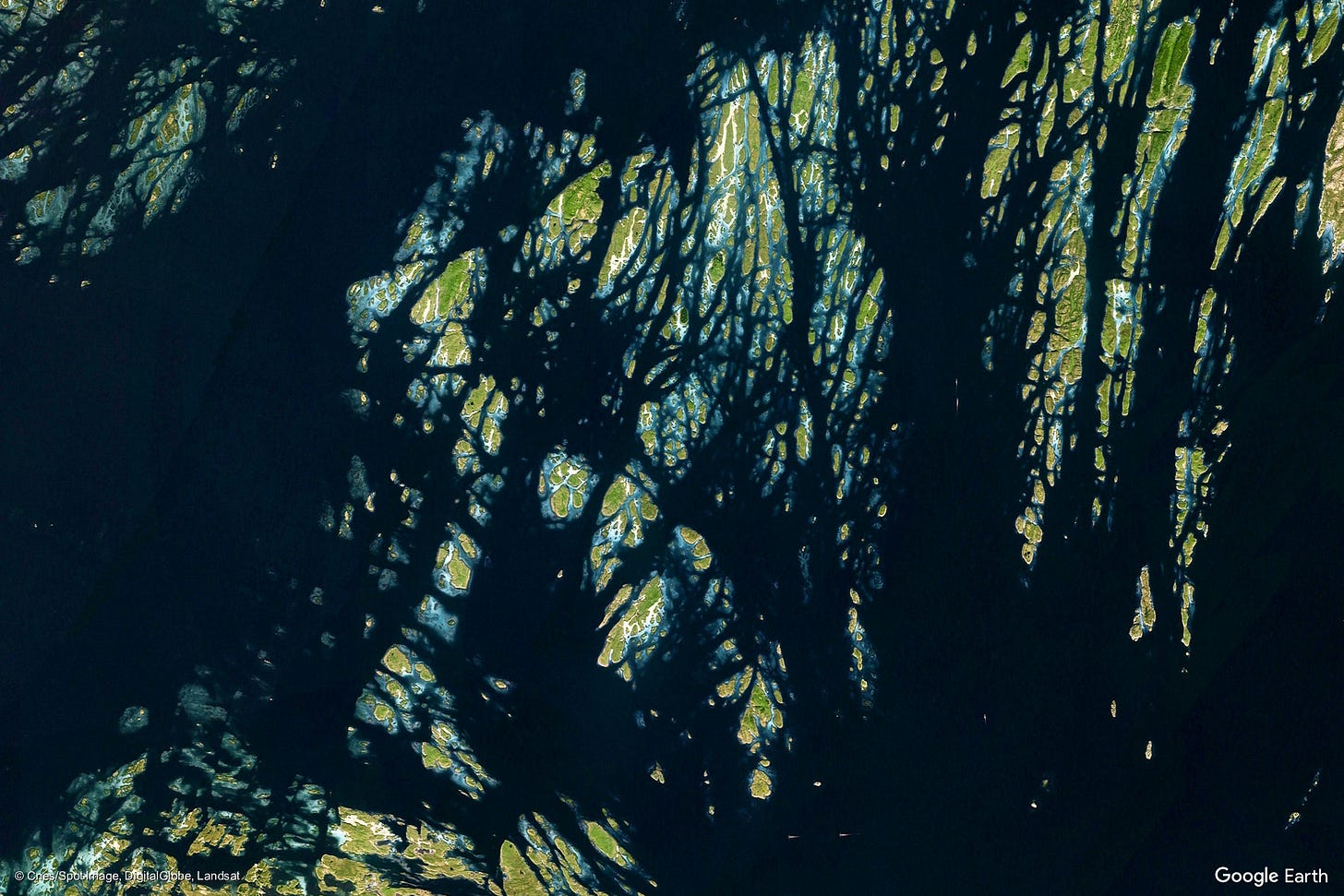

Though many of the reports about nature returning were false, such as dolphins in the Venice canals, the ideology behind this belief is worth discussing. The “nature is returning” meme relies on the belief that humans and nature are separate, which is blatantly untrue. Humans are very much a part of nature, not apart from it.

In today’s issue of Placeful, I will be writing a bit about the history of this ideology of separation, the usefulness (for some) of maintaining it, and a timely story about humans and reindeer. It’s a long one, but I hope you enjoy!

Understanding the origin

The ideology of separation between humans and nature has a complex history. The subject could be (and probably is) the subject of an entire book. So let’s start with one specific book—the Bible.

Every culture has an origin story (whether believed literally or figuratively) outlining their purposeful beginning on this planet. Among Christians, the dominant religion of the Western world, this is the book of Genesis. The King James version (authorized in 1611) of Genesis 1:26-28 reads:

And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

In an influential article from 1967 titled “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,” Lynn White writes about the long-term repercussions of the language presented above.

Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. As early as the 2nd century both Tertulian and Sant Irenaeus of Lyons were insisting that when God shaped Adam he was foreshadowing the image of the incarnate Christ, the Second Adam. Man shares, in great measure, God’s transcendence of nature. Christianity, in absolute contract to ancient paganism and Asia’s religions . . . not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends. (p. 1205)

Western beliefs, many based in Christian ideologies, have given generations of people permission to view the world as a land of bounty made purposefully and only for humans. This understanding of our place in the world demotes and devalues all other living and nonliving things. Though not all Christians share this ideology, it is the nonetheless important to recognize its prevalence and long-term impact. This is just the start.

This land is my land

Land ownership and other cartographic designations of “mine versus yours” also contribute to this ideology, which could arguably be traced back to the previous section. It is difficult to marry the ideology of land ownership and dominion over the land with the ideology of shared responsibility.

Our piecemeal Western approach to land caretaking contributes to the perceived seperation between people and nature, and the result is that everyone and no one is responsible for the wellbeing of the commons.

Here is Brian Kahn’s take on the issue of artificial boundaries and our resulting attitudes, pulled from an interview for On the Media from last April:

As a former park ranger, I am a big believer in National Parks. I love them, but there's this kind of classic idea that nature exists within these parks. The boundary is there. Outside of that it's the terrible human world. [W]e may draw boundaries on a map to show where a National Park exists, but the atmosphere doesn't respect those boundaries and certainly other humans influences don't respect them either.

We all drink the same water, breathe the same air, and depend on the health of soil miles away from our homes to be nourished. We are an interdependent part of these systems, regardless of property lines or borders.

The economy, too

In the pursuit of prosperity, our current economic system encourages the exploitation of the environment. For many industries, especially those in the business of resource extraction, it is beneficial to perpetuate the myth of separation. We wouldn’t want to hurt ourselves, so we make mental loopholes, justifying the level of our impact by its perceived distance from ourselves.

There are many forces at work preventing us from feeling like we are a part of the environment—or even desiring to feel a part of it. The alternative, though, is to continue down the path we are on and jeopardize the future habitability of this planet for many species, including us.

A convenient dichotomy

The ideology of separation makes it easier to justify choices that cause harm to the environment. Ultimately, though, we depend on the earth’s natural processes for our own survival. Individual wealth—the end goal of many harmful industries—will only delay the effects of inaction for some. No one is immune.

[T]he reality is that we aren’t separate from nature. Far from it. Digging up oil, turning land over to monocrops, overfishing, and rampant pollution all threaten to upend our world and everything in it. In fact, each extra puff of carbon pollution and piece of single-use plastic that ends up in the ocean ties our fate ever tighter to that of the planet. Eventually, all that carbon dioxide will push seas higher and inundate our homes. And the plastic will choke out the natural world, leading to deserted oceans and dried up livelihoods. - Brian Kahn, Gizmodo, April 2020

Humans have made some pretty terrible choices when it comes to the sustainability of our existence here on earth, but our impacts are not all bad. In fact, there are many natural processes that depend on humans; these give me hope that a more balanced give and take is possible.

Looking solely through the lens of evolutionary success, many species depend on us. Corn and other food crops depend on human cultivation and seed saving for the continuation of their species. Our relationship to the plants and animals of the earth is, in some cases, written on their DNA, and ours, too.

A story about people, reindeer, and the tundra

This week’s episode of Living on Earth, an environmental podcast, featured an interview with Judith D. Schwartz, author of the book The Reindeer Chronicles: And Other Inspiring Stories of Working with Nature to Heal the Earth (which I am looking forward to reading in the New Year). I wanted to share a bit of the interview because it is a great example of a positive, long-term relationship between people and the earth, involving the indigenous Sámi reindeer herders of Northern Europe and parts of Russia.

Schwarts: [F]or thousands of years, Sámi reindeer herders have been moving their animals across the far north. [T]hey have summer terrain, and then they have winter areas. So they move the animals to different spots depending on the season.

[T]he Norwegian government was operating on the assumption that, "well, if there are more animals, well, you know, that's bad for the environment. So we need to ask or demand that these reindeer herders lower the numbers of reindeer." But the truth is that the way that the Sámi herders have been managing their animals, in fact, helps to maintain the tundra ecosystem.

So here's how it works. [W]ith the summer herding, the reindeer are browsing, they are nibbling at shrubs and small trees. And the reason that that's important is that the native heath, the kind of grassy areas that has a higher albedo, which means that it reflects the heat. However, these shrubs and trees, they have a lower albedo, which means they retain the heat. [W]hen they get established, that can heat up a whole microclimate. Okay, so that is adding heat to the landscape. But because the reindeer are nibbling at those plants, they're keeping them in check, so that they don't have that heating impact.

[I]n the winter, the reindeer in large numbers are moving across the snow, and their hooves are pressing down the snowpack. And while that initially sounds like a negative thing . . . actually, the snow had been acting as an insulator. So it was . . . protecting the soil from the deep chill. But when the reindeer press down the snow, that means that the soil stays frozen, the permafrost stays frosty, so they are maintaining the cold. [T]hat is important, especially in an area near the poles that is warming faster than other parts of the world.

In Norway and adjacent countries, the relationship developed over thousands of years between people and reindeer has been keeping the tundra cool, protecting this special ecosystem and, ultimately, our planet’s climate. This is one story among many of how plants, animals, and people can support each other, and how human impacts on the environment are not destructive by default.

Reuniting with nature

In the current age of environmentalism, separating ourselves from nature serves as an emotional safety blanket, a way to hide from the guilt of our inaction. However, it also chips away at our relationship with place, and blocks a feeling of connectedness and purpose.

Let’s ask ourselves, what does it mean to be a part of the natural world? To be in relationship with the simultaneously mundane and extroardinary objects and beings sharing this planet with us?

Separating ourselves from nature, I believe, prevents us from fully appreciating our ecological role. We are not the virus. We belong. Our relationship just needs a little work.

I’ll be taking a holiday break next week and look forward to connecting with you all after the New Year. From my little corner of the world to yours, happy holidays. I hope you find time to celebrate what is important to you during this time of year, and always <3

With love,

Emily

Placeful Practice

Outline three clear examples, broadly or in your own life of interdependence within the natural world. For example, the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between animals and plants!

If you want to go even further, I highly suggest reading Lynn White’s article quoted earlier, “The Historic Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis.” It was required reading for me in college; the article is definitely dense, but totally fascinating.

Placeful is a weekly email newsletter containing personal narratives and reporting on sense of place and sustainability. Each week I delve into a new topic, wrapping it up with an action item that will help readers foster deeper connections to the natural, cultural, built, and historic environments around them. Read more about Placeful.

To find a web version of this issue, click here. Know someone who would appreciate the topics I’m writing about? Please share! If you’d like, you can follow me in twitter (@emily_ann_again) or Instagram (@emily.a.roberson). And lastly, if someone forwarded this to you, subscribe below to receive future issues straight to your inbox. Thanks for reading <3