Placeful is a weekly newsletter exploring sense of place, sustainability, and the actions we can take to more deeply engage with our communities and wild spaces. Each week covers a new topic. To learn more about the “why” behind Placeful, start here.

Any books mentioned in this issue can be found on my bookshop shelf. I may earn a commission from books purchased through these links, at no additional cost to you.

Early in the pandemic, a task force of people in the Moab area organized. Their goal? To make sure at-risk and older adults in our community could still access food. One of their early successes was organizing a network of volunteers to purchase and deliver groceries to these individuals.

Though the need for the service eventually declined due (I think) to online grocery pick-up, the group recognized how vulnerable some of our citizens were to the virus and how they might be able to mitigate their risk of exposure. Across the U.S., other communities were doing the same. Additionally, other mutual aid networks organized to help folks with late rent payments, child care, translating crucial public health information, navigating the unemployment application process, and other needs that could not always be solved through governmental or institutional bodies in a quick and responsive way.

Many of our lives have changed drastically due to the pandemic. Some have lost loved ones, others have lost their livelihoods, and many have suffered from loneliness or anxiety. A lot is still uncertain while we wait for wider access to the vaccine, but one thing that has become abundantly clear during all this is how much we depend on one another.

Like the grocery delivery network that sprouted up here in Moab, many neighborhoods and communities around the U.S. and the world have, in response to the pandemic and its many social and economic consequences, turned to mutual aid networks for support.

In today’s issue of Placeful, I’ll be discussing the ins and outs of mutual aid—what it is, its history, and why this relatively unknown concept is having a (very necessary) moment.

In the spirit of empowering the people we share and love our communities alongside, let’s dig in.

What is mutual aid?

Mutual aid is both complex and extremely simple, hard to define but easy to understand. Ultimately, it’s people helping other people, stepping up to ensure their health and safety when other systems aren’t working.

As Sigal Samuel puts it, “Mutual aid centers around the idea that we should all share with each other reciprocally and that we can help meet one another’s needs in a self-directed, grassroots way, rather than relying exclusively on top-down government solutions that may come too slowly, or fail to offer adequate support to the most vulnerable people.” (Vox, Apr. 2020)

Activists and community organizers have been working in this space for a long time and have developed very in-depth understandings. Below is a definition from Dean Spade, an organizer who built and maintains the mutual aid resource website Big Door Brigade:

Mutual aid is when people get together to meet each other’s basic survival needs with a shared understanding that the systems we live under are not going to meet our needs and we can do it together RIGHT NOW! Mutual aid projects are a form of political participation in which people take responsibility for caring for one another and changing political conditions, not just through symbolic acts or putting pressure on their representatives in government, but by actually building new social relations that are more survivable. Most mutual aid projects are volunteer-based, with people jumping in to participate because they want to change what is going on right now, not wait to convince corporations or politicians to do the right thing. (This definition continues and is very thorough, keep reading here if you are interested)

You can also define mutual aid by clarifying what it is not. Mutual aid is not, according to a toolkit put together by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and organizer Mariama Kaba, “quid pro quo transactions, only for disasters or crises, charity or a way to ‘save’ people, [or] a reason for a social safety net to not exist.”

Below is a wonderful graphic from the same resource, designed by Becca Barad.

One example of a mutual aid group is the Tacoma Mutual Aid Collective in Washington. Over the last few months they have done so much to support people experiencing homelessness in their local area, including providing hot meals and winter weather supplies, organizing donation drives, funding laundry days (including transportation to laundry facilities), and other actions that are direct responses to the needs of their community. Groups like this exist all over the place.

Why mutual aid?

Mutual aid is a response to people’s survival needs not being met through other means. At the very top, this means that mutual aid is a response to ineffective or nonexistant social safety nets, but on a practical level, it looks like people looking out for one another.

Below are three examples of why I believe mutual aid networks are re-entering the collective conscious, and a little bit of history, too.

Fewer people are attending religious services

As many folks are aware, fewer people each year are affiliated with a religious group, which I believe has consequences for local mutual aid efforts. Importantly, religious services are one way that people connect with each other within a local community, and they also serve as a group that people belong to—an important aspect of identity formation.

Here’s just one example: from 2007 to 2018/19, the number of people identifying as Christian in the U.S. shrunk from 78% to 65%, while the number of people that claimed no religious affiliation rose from 16% to 26% (Pew Research Center).

I speculate that as more Americans become religiously unaffiliated, fewer will have access to the structured religious communities that have a spoken or unspoken commitment to mutual aid, and the subsequent religious social support members receive through participation.

Mutual aid groups have existed within religious organizations for a long time (whether defined as such or not). For those who are unaffiliated, however, I believe that the quickly popularizing secular mutual aid networks can fill in the gap.

Declining social infrastructure

When our towns and cities are not designed in such a way that encourages social connection (accessible walkways, public libraries, schools that encourage parent participation), we all lose. Formalized mutual aid networks become an answer when informal, less defined networks are not easily developed over time.

Take, for example, Eric Klinenberg’s description in Palaces for the People of resilient neighborhoods during the Chicago heatwave of 1995. Here he is describing why some neighborhoods experienced fewer deaths, even though other variables (like income-level) were the same:

During the decades that residents fled neighborhoods like Englewood, Chicago’s most resilient places experienced little or no population loss. In 1995, residents of Auburn Gresham walked to diners, parks, barbershops, and grocery stores. They participated in block clubs and church groups. They knew their neighbors—not because they made special efforts to meet them, but because they lived in a place where casual interaction was a feature of everyday life. During the heat wave, these ordinary routines made it easy for people to check in on one another and knock on the doors of elderly, vulnerable neighbors. “It’s what we always do when it’s very hot or very cold here,” says Betty Swanson, who has lived in Auburn Gresham for nearly fifty years . . . And with heat waves becoming more frequent and more severe, living in a neighborhood with a social infrastructure like Auburn Gresham’s is the rough equivalent of having a working air conditioner in every home. (p. 6-7)

Many lives were saved because the neighbors knew each other—made almost automatic through community design—and checked in. Since many people don’t recognize the early onset of heatstroke in themselves, this means people got help faster, or received preventative assistance before getting to that point.

Democrats and Republicans agree that American infrastructure needs work. Not just our hard infrastructure like roads and water pipes, but also investments in parks, walkways, and public transit that make communities better and healthier places to live.

Informal mutual aid is easier when our cities keep us connected by design. Formalized mutual aid is one response to lacking social infrastructure.

Organized mutual aid efforts help people help each other, and show our government how to do it better in the process

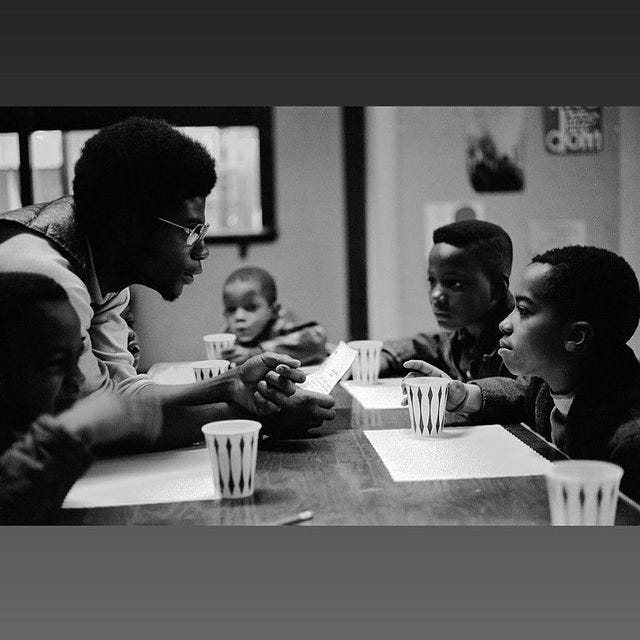

One well known example of mutual aid began in 1969. Tens of thousands of children participated in the Free Breakfast for School Children program, organized by the Black Panther Party (BPP) first in Oakland, and then in multiple cities across America. Kids who were going to school hungry received a healthy meal before school, allowing them to focus more on their studies—a radical but simple act that met the needs for their survival.

However, the free lunch program didn’t go unnoticed by the FBI, which was working actively at the time to undermine the BPP’s efforts. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI at the time, said the program was “potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.” They began a campaign to destroy the free breakfast program.

FBI agents went door-to-door in cities like Richmond, Virginia, telling parents that BPP members would teach their children racism. In San Francisco, writes historian Franziska Meister, parents were told the food was infected with venereal disease; sites in Oakland and Baltimore were raided by officers who harassed BPP members in front of terrified children, and participating children were photographed by Chicago police.

“The night before [the first breakfast program in Chicago] was supposed to open,” a female Panther told historian Nik Heynan, “the Chicago police broke into the church and mashed up all the food and urinated on it.” (Erin Blakemore, History.com)

The USDA were piloting free breakfast programs since the 1960’s, but it wasn’t until the BPP’s Free Breakfast for School Children program was threatened and ultimately shut down in the early 70’s that it was authorized throughout the U.S. in 1975.

In this case, a local organization met a community’s survival need by feeding its youngest community members, allowing them to study undistracted and in good health. This in turn had lifelong benefits for the recipients in both health and educational attainment, which benefitted these communities immediately and in the long-term: mutual aid paying off in increased quality of life for all (and showing our government how it’s done in the meantime).

How to get involved in a mutual aid network

This not a comprehensive list by any means, but here are a few resources for jumpstarting this work in our communities—or better yet, joining others who have already set the foundations.

AOC and Mariama Kaba’s Mutual Aid 101 toolkit, drafted in response to COVID

Idealist.org’s searchable tab for Mutual Aid Groups from across the world

This Bloomberg CityLab article, “‘Solidarity, Not Charity’: A Visual History of Mutual Aid,” is fascinating and provides much more context than I ever could here

Dean Spade’s website Big Door Brigade and book Mutual Aid

This Mashable article goes in depth about resources and best practices for organizing mutual aid groups online during COVID times

Solidarity not charity

The goal of writing about mutual aid today is for us to think about the sociopolitical context that has made them important—before, during, and after COVID—and to empower us to look for ways we might be able to organize or participate in this kind of work.

Formalized (but not professionalized) mutual aid networks are especially important for those in our communities who are newly transplanted, who may not have access to the right social supports for a number of reasons, or for whom social supports don’t exist. Whether this is due to economic struggles, differences in language, lack of available child care slots, or institutionalized racism, mutual aid groups are getting the work done in our communities.

The barriers to stability here in the U.S. are astounding, and most of us are not immune to needing help now and again. Mutual aid is a simple but radical way to stand in solidarity with one another on a very practical level. Whether it’s delivering groceries to an at-risk neighbor, or donating an extra winter coat, we all can play a role in lifting each other up.

Mutual aid is another way—in a long list of ways—to practice placefulness, and to do it in solidarity with the people who also love the places that we love.

With love,

Emily

Placeful Practice

Joining or organizing a mutual aid network might not be for everyone. Either way, this week’s Placeful Practice is to read one of the aforementioned resources. I think the “Visual History” piece is a great place to start.

I also encourage you to reflect on mutual aid that you may already be participating in in your own life.

If you have any additional thoughts about mutual aid as a concept, resources for people looking to kickstart one, or examples of great mutual aid projects in your area or across the world, please leave a comment—I’d love to hear them, and I’m sure others would, too! Also, always open to feedback at placeful.emily@gmail.com.

Somewhat unrelated, but cool

If you like discussions about sustainability, and especially if you like actionable tools for combating climate change, I highly encourage you to check out the new newsletter The Green Fix. And if you end up subscribing, let me know!

Placeful is a weekly email newsletter containing personal reflections and reporting on sense of place and sustainability. Each week I delve into a new topic, wrapping it up with an action item that will help readers foster deeper connections to the natural, cultural, built, and historic environments around them. Read more about Placeful.

To find a web version of this issue, click here. Know someone who would appreciate the topics I’m writing about? Please share! If you’d like, you can follow me on Twitter (@emily_ann_again) or Instagram (@emily.a.roberson). My inbox is always open at placeful.emily@gmail.com. And lastly, if someone forwarded this to you, subscribe below to receive future issues straight to your inbox. Thanks for reading <3